Chapter 9

Scientism and religion

9.1 Militant atheism

The relationship between religion and the

natural sciences, as we have noted in some previous chapters, is

currently of great social significance. It is the subject of ongoing

legal battles, the focus of concern about education, and a topic that

provokes passionate debate. There has over the past decade been a

spate of aggressive atheist polemic books arguing that religious

belief is disproved by science, explained away by science, and in any

case intrinsically evil. The phrase recently used most widely to

denote these polemics is `the New Atheism'. We'll have a little bit

more to say about the extent to which their arguments are new; but

certainly they are immoderate, dismissive, disdainful, and

discourteous. Some have called them `hysterical atheism', but let's

settle for a more neutral adjective, `militant'171. These militant atheist

arguments are notable for their assertive scientism. We will examine a

few examples.

Science disproves religion

Richard Dawkins' The God Delusion is

perhaps the best known of the militant atheist books of the early

twenty-first century. In it Dawkins is pretty much as direct as he can

be. About the existence of God he writes "Either he exists or he

doesn't. It is a scientific question; one day we may know the answer,

..."172

Or again, "Contrary to [T.H.] Huxley, I shall suggest that the

existence of God is a scientific hypothesis like any other. ... God's

existence or non-existence is a scientific fact about the universe,

discoverable in principle if not in practice."173

Actually Dawkins' book does not "suggest", or even argue, it

assumes, and repeatedly asserts that the question is a scientific

question. For example he later states "The presence or absence of a

creative super-intelligence is unequivocally a scientific question

..."174

It then goes on at length to try to show that, regarded as a scientific

question, the existence of God has poor evidence in its support. The

question of the strength of the evidence is important but that's not

what I want to focus on. I am drawing attention to the remarkable fact

that Dawkins asserts that the existence of God is a scientific

question. Why so remarkable? Well, if there were ever any meaningful

distinction between "scientific" questions and other possible types

of question, surely the distinction between scientific, physical

questions (about nature) and metaphysical questions (about God)

is the most obvious and traditional one. But Dawkins does not even

bother to acknowledge the possibility of such a distinction. Instead

he castigates those who regard themselves as agnostics as failing to

pay attention to the scientific evidence (or lack thereof) in forming

their theological opinions.

But since the existence of God has, from time immemorial, been

considered not to be scientific question, or, to express it less

anachronistically, not a question of natural philosophy, how can

Dawkins get away with a bald assertion to the contrary? It is because

he is relying on the widespread acceptance of his scientistic outlook,

even among those who disagree with his theological views. The

reference to "scientific fact" betrays his implicit assumption that

all significant "facts" are scientific. Otherwise, it would be just

as sensible to assert that the existence or non-existence of God is a

historical fact, or a legal fact, or a sociological

fact, or a religious fact.

In criticizing evolutionary paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould's

avowed agnosticism and

"Non

Overlapping Magisteria" approach to the relationship between science

and religion, Dawkins betrays himself

further. He is at pains to oppose Gould and other scientists who draw

back from using science to dictate metaphysical conclusions, because

he thinks their reticence is motivated by the attitude "theologians

have nothing worthwhile to say about anything else; let's throw them a

sop and let them worry away at a couple of questions that nobody can

answer and maybe never will."175

Then he is overtaken by his own rhetoric in questioning

Gould's de facto atheism by asking "On what basis did he make

the judgement, if there is nothing to be said about whether God

exists?"176

Again this is elementary scientism at work. Actually, although Gould

betrays his own substantial scientism by implying that religious

matters are not matters of fact, he never asserts "there is

nothing to be said about" God's existence. Gould's position appears

to be that science does not prove or disprove it. Dawkins'

"nothing to be said" reinterpretation of Gould is a distortion of

his position, one that could be overlooked only by someone who

completely takes for granted that the only sound basis for judgement

is science. In other words, Dawkins' whole viewpoint is sustained by

overriding scientism; without it his arguments are utterly hollow.

About questions of the historicity of Biblical events such as the

resurrection, Dawkins says "There is an answer to

every such question, whether or not we can discover it in practice,

and it is strictly a scientific answer. The methods we should use to

settle the matter, in the unlikely event that relevant evidence ever

became available, would be purely and entirely scientific methods."

Well, actually, no. These are questions about history. Natural science

is almost completely powerless to answer historical questions about

unique events of human history. If you insist that there is no useful

evidence except that of "purely and entirely scientific methods",

then of course there is not going to be such evidence. But that's not

all the evidence that historians consider for these or for any events

of history. Only a blatant scientism would insist on "purely and

entirely scientific methods" for historical matters.

Science explains the mind

The

evolutionary psychologist Steven

Pinker

is a more multidimensional figure in the

scientistic front line. His book How the Mind Works is a an

eclectic smorgasbord of ideas and opinions ranged artistically around

the main course consisting of the advocacy of the computational theory

of mind and of evolutionary psychology. Pinker contradicts many of the

more mechanistic approaches to psychology such as Behaviorism. The

"big picture" he says is "that the mind is a system of organs of

computation designed by natural selection to solve the problems faced

by our evolutionary ancestors in their foraging way of life."

The computational theory of mind is that "beliefs and desires are

information, incarnated as configurations of symbols. The

symbols are physical states of bits of matter, like chips in a

computer or neurons in the brain... the symbols corresponding to one

belief can give rise to symbols corresponding to other beliefs ... The

computational theory of mind thus allows us to keep beliefs and

desires in our explanations of behavior while planting them squarely

in the physical universe.

It allows meaning to cause and be caused."177

"Beliefs and desires" as information is innocuous enough. Something like

this `computational' description (vague though it is) may well turn

out to reflect reality, though science is a very long way from

demonstrating that it does. More positively, Pinker clearly

acknowledges that beliefs and desires can't possibly be excluded

from a description of the actions of humans (or animals) without

making nonsense of what we know introspectively to be the case for

ourselves, and what we routinely use with great success to explain the

behavior of others.

The evolutionary part of the argument, which is its major subject, is

less persuasive. Pinker echoes Dawkins in saying "Natural selection

is the only explanation we have of how complex life can

evolve..." and dismissing teleological explanation with

"One of the

reasons God was invented was to be the mind that formed and executed

life's plans. The laws of the world work forwards, not backwards: rain

causes the ground to be wet; the ground's benefiting from being wet

cannot cause the rain. What else but the plans of God could effect the

teleology (goal directedness) of life on earth? Darwin showed what

else."178

This forwards-causality argument sounds plausible. But let's

dig a bit deeper. Consider irrigation; it is precisely an example of

the ground's benefitting from being wet causing the `rain'.

Irrigation does not happen to concrete patios, rocky outcrops, or

lakes. Neither theist nor atheist attributes crop irrigation to

something supernatural. It is attributed to the intentionality of the

human agents that implemented it. But Pinker's argument dismissing

God could equally well be applied as follows "One of the reasons

human mind was invented was to be the mind that formed and executed

life's plans. The laws of the world work forwards, not backwards: rain

causes the ground to be wet; the ground's benefiting from being wet

cannot cause the rain."

Does Pinker really mean to imply, as his argument does, that we are in

error when we speak of human

intentionality as a cause? Presumably

not, since he has allowed "beliefs and desires" as explanations. But

then why is the intentionality explanation disallowed when God is

referenced? Perhaps the Darwinian theory removed the necessity

to posit a Creator, at least in respect of biological diversity, but

it hardly rules one out. It disabled the argument from design as far

as it is based on biological adaptation. Perhaps, by Dawkins'

memorable overstatement, "Darwin made it possible to be an

intellectually fulfilled atheist", but he did not make it impossible

to be an intellectually fulfilled theist.

It seems that if Pinker, and those who argue in the same way, concede

that humans and their intentionality are part of nature, then as a

consequence there can in nature be such a thing as "backward

causation", call it teleology, purpose, or intentionality. Either

that or he must reverse his opinion that human intentionality is a

process of the physical universe. He's trying to have it both

ways. But either explanation in terms of intentionality is permitted

by natural science, or else human (as well as divine)

intentionality is ruled out in scientific explanations. Both Pinker

and I think that intentional teleological explanations are not part of

science's methods, that the laws of science do "work forwards, not

backwards". My position is that intentionality is nevertheless a

perfectly acceptable (indeed obvious) way to understand many

phenomena, but that it is part of non-scientific knowledge and

explanation. Pinker however is trapped in a contradictory

scientism. Scientism's argument against God amounts in summary to the

following.

Purpose and personal agency is deliberately omitted

in science's descriptions of the world. All real explanations are

scientific explanations. Therefore all real explanations are

impersonal; God, being personal, is not a real explanation. Impersonal

evolutionary explanation remains.

But this argument, whether Pinker

likes it or not, applies equally to any explanation in terms of human

agency. It rules out human purpose as a valid explanatory factor,

which seems to me, and to many, as a disqualifying fault.

A key weakness of evolutionary psychology is that it makes even fewer

specific predictions than biological evolution. It is generally

content instead with composing stories that are purported to explain

some fact of psychology in terms of a hypothesized evolutionary

history. In most cases such stories are independent of other

phenomena. They are not integrated into a scientific explanatory web

that would make them a robust part of theory; they are

subject-specific, and regularly sound like special pleading or mere

speculation. In this respect they contrast with evolutionary

explanations of biology and physiology, some of which do gain strong

plausibility from serving as consistent integrated explanations of

multiple phenomena. Evolutionary psychologists often cite successes of

evolutionary explanation in physiology or physical biology as

arguments in favor of evolutionary psychology. This seems a

non-sequitur. It is perhaps appropriate to explore the degree to which

evolution can be extended to explain psychology, but sometimes the

evolutionary enthusiasm of the advocates gets the better of them. For

example, Pinker sets out to counter the claim that "natural selection

is a sterile exercise in after-the-fact storytelling" by quoting Mayr

The adaptationist question, "What is the function of a given structure

or organ?" has been for centuries the basis of every advance in

physiology. If it had not been for the adaptationist program, we

probably would still not yet know the functions of thymus, spleen,

pituitary, and pineal. Harvey's question "Why are there valves in the

veins?" was a major stepping stone in his discovery of the circulation

of the blood179.

And Pinker immediately goes on "... everything we have learned in biology

has come from an understanding, implicit or explicit, that the

organized complexity of an organism is in the service of its survival

and reproduction."

Pinker's escalation of Mayr's already hyperbolic claim is based on a

fundamental confusion. He is confusing the search for function,

which has indeed been a vital principle of biology for millennia, with

Darwinian adaptation. Notice that when Mayr wrote about what

had been the case "for centuries", it was only 123 years after

Darwin's "Origin" was published. His example of the circulation of

the blood dates from Harvey's notes in 1615. So Mayr could not

justifiably have meant Darwinist when he said adaptationist. He

presumably meant nothing more than that organs have valuable functions

and we learn most by looking for their function. Certainly adaptation,

in the sense of fitness to the environment, was noted long before

anyone thought to address it in terms of evolution. But for the

purpose of his argument Pinker makes the further unjustified leap that

all biological knowledge comes from a focus on survival and

reproduction, on a Darwinist program. He's implying in effect that,

even before Darwin, biology proceeded only by a closet ("implicit")

Darwinism. That is a ludicrous attempt to have it both ways.

Darwin's ideas made a big difference to the progress of biology, but you

can't prove it by saying that centuries before his time scientists

were dependent on those ideas by some mysterious `implicit' process.

The sort of psychological explanation that Pinker favors, which would

escape the just-so-story criticism, is when predictions are made on

the basis of evolutionary arguments, and prove to be correct. To cite

such occasions is a principled approach to trying to demonstrate his

case. How convincing is it? Here's one example concerning the question

"How do parents make Sophie's Choice and sacrifice a child when

circumstances demand it? Evolutionary theory predicts that the main

criterion should be age ... right up until sexual maturity." In

order to try to validate the `prediction' based on life expectancy,

that parents would not sacrifice an older child when a younger one is

born (actually a postdiction, since this is already an observation in

all existing cultures) he offers this. "When parents are asked to

imagine the loss of a child, they say they would grieve more for older

children, up until the teenage years. The rise and fall of anticipated

grief correlates almost perfectly with the life expectancies of hunter

gatherer children."180

This "almost perfectly" is an almost perfectly

gratuitous claim of numerical correlation that can't possibly be

backed up. Grief can't be unambiguously quantified or measured. It

obviously does not possess the Clarity required for such

quantification. That's quite apart from the fact that the life

expectancies of

hunter gatherer children from prehistory are

thoroughly speculative. Pinker refers to them (strangely) as

"actuarial tables", although he appears to mean three numbers

derived from guesses at mortality rates.

Pinker devotes two pages to birth-order arguments like this, which by

the way, even his own sources acknowledge to be considered by the

majority in the field as a "mirage"181.

Just pause for a moment from

the evolutionary enthusiasm and consider the possibility that parents

feel the way they report, not because of some evolutionarily

programmed survival calculus, but because they realize that their love

for their children grows through the shared experiences of their years

together. This seems a far more sensible explanation, but of course it

doesn't have the honorific of being scientific, or evolutionary. I

suppose that is why Pinker prefers his actuarial tables.

When it comes to religion, Pinker no longer offers anything even as

feeble as this in support of his opinions. "What we call

religion in the modern West", he opines, "is an alternative culture

of laws and customs that survived alongside those of the nation-state

because of accidents of European history."182

A profoundly ill-informed

remark like this about the roots of western culture hardly constitutes

an argument. It is of a piece with his purely rhetorical litany

of the evils and self-interest of religion. Referring to witches,

shamans, ancestor worship, the Bible, rites of passage, and so on, we

are informed that although "Religion is not a single topic", it

"cannot be equated with our higher, spiritual, humane, ethical

yearnings". Clearly Pinker wants to leave the field free for ethics

and `spirituality' without having the unpleasantness of religion. We

get the picture. He's against religion. But it would have made his

diatribe more an integral part of his exposition of evolutionary

psychology if he'd actually offered some evidence relating the two.

Without it, we are in a position analogous to that of the two Victorian

parishioners discussing the week's sermon:

"What was the sermon about?"

"Sin."

"And what did the Vicar say?"

"He was against it."

Pinker is of course completely at liberty to advocate his opinions

about what people believe and why they believe it. In the case of

religion he doesn't seem to think that he needs any justification for

those opinions. In the case of many other beliefs, his book offers

evolutionist stories in justification, or explanation, of his opinions

about them. In all too many cases those justifying stories appear to

be just-so stories, plausible sometimes - sometimes not - but hardly

compelling, falling far short of what most scientists consider

demonstration demands, yet all too often spuriously portrayed as some

kind of scientific consensus, rather than what they are: his opinions.

Evolutionary psychology seems to draw much of its momentum from a

fundamentalist scientism, which regards naturalist explanation as the

only explanation worth having - even of the human mind and

society. It has appeal as a way to incorporate consciousness and

culture into a scientistic world-view, especially for those who want a

stick with which to beat religion. But it falls far short of the

convincing explanations science offers of the physical world, of

nature. And it must do so, because much of psychology does not possess

the characteristics that are required for scientific analysis.

Science explains away religion

Daniel Dennett, even though he is a philosopher, not a scientist, does

try to offer evidence that relates evolutionary psychology to

religion. Indeed, his Breaking The Spell. Religion as a Natural

Phenomenon sets out to argue that religion is convincingly

explained by evolutionary arguments about human psychology, and that

it is thereby debunked.

Right from the outset, Dennett wants to draw on, and exploit indirectly,

descriptions of the natural world for his argument. Religion is to be

understood as analogous to a parasite invading our brains, causing us

to set aside our personal interests in order to further the interests

of an idea: religion. For his purposes, Dennett defines

religions as

"social systems whose participants avow belief in a

supernatural agent or agents whose approval is to be

sought"183: a

definition, as he readily admits, crafted to avoid the "delicate

issue" that the scientism that permeates his views is arguably a

religious commitment and certainly a metaphysical commitment. Let's pass

quickly over the difficulty that his definition excludes Confucianism,

Buddhism, most Deism, and sundry other obviously religious teachings

from its scope.

"Eventually", says Dennett, "we must arrive at questions about

ultimate values, and no factual investigation could answer them". But

it is "high time that we subject religion as a global phenomenon to

the most intensive multidisciplinary research we can

muster..."184. Even

though (three pages later) this "might" break the spell of

religion, we must carry out a

"forthright, scientific, no-holds-barred investigation of religion as

one natural phenomenon among many."185

Wait a minute, though, what just

happened to "questions about ultimate values", or

"multidisciplinary"? Well, any scientific discipline is

allowed, I guess. In Dennett's view the neglect of this scientific

program has been because of a

"largely unexamined mutual agreement that scientists and other

researchers will leave religion alone"186, but now we need to "set about studying religion

scientifically".

The study of religion as a natural phenomenon, Dennett asserts, is no

more presupposing atheism than is the study of Sports as a

Natural Phenomenon or Cancer as a Natural Phenomenon. The

metaphor gets a bit out of hand when sports "miracles", by a strange

transition, become the topic. But a miracle, and presumably by

extension all of religion, requires us to "demonstrate it

scientifically"

Was Gould right that there is a boundary between two domains of human

activity? Dennett shows his identification of "scientific"

with "factual" by saying, "That is presumably a scientific, factual question,

not a religious question"187.

Dennett shares in the disingenuousness of most of the militant atheist

writers when he bemoans the neglect of this project as caused by

academic distaste begotten by biased prior studies, and portrays

himself as representing a small band of "brave neuroscientists and

other biologists who have decided to look at religious

phenomena"188. The embattled

potential-martyr self-portrait - even though he's not the first to

paint it - is not particularly convincing for a best-seller author

on the fashionable anti-religion band-wagon.

Dennett spends significant effort confronting the [supposed189]

"worry that such an investigation might actually kill all the

specimens" [of religion]. In the process we learn that

"music is another natural phenomenon ... but is

only just beginning to be an object of the sort of scientific study I

am recommending", by which he means for example "why is it beautiful

to us? This is a perfectly good biological question."190 It does not

appear to cross Dennett's mind that there might be structural or

methodological reasons why scientific study of non-scientific

topics like music and religion are circumscribed. His concern is to

combat what he thinks is simply the "propaganda ... from a variety of

sources" that religion is "out-of-bounds".

Dennett thinks that goods (moral and physical), for which he instances

deliberately problematic cases: sugar, sex, alcohol, music, and money,

can anchor their value only in "the capacity of something to provoke

a preference response in the brain quite directly."191 A co-evolutionary

"bargain that was struck about fifty million years ago between plants

blindly "seeking" a way of dispersing their pollinated seeds, and

animals similarly seeking efficient sources of energy" explains

"sharpening our ancestors' capacity to discriminate sugar by its

"sweetness." " All values "started out as instrumental", as a

biologically programmed preference conferring survival value, and

"The same sort of investigation that has unlocked the mysteries [sic]

of sweetness and alcohol and sex and money" needs to be applied to

religion.

The argument here becomes puzzling and self-contradictory, which makes

it hard to summarize. On the one hand a biologically costly activity

(like religion) can persist only if "it somehow provokes its own

replication ... to ask what pays for one evolved biological

feature ... nicely captures the underlying balance of forces observed

everywhere in nature, and we know of no exceptions to this

rule"192. [Emphasis his. Actually

organs like the human appendix are such exceptions if they are truly

vestigial, as one major evolutionary argument maintains.] On the

other hand, the spectrum of possible evolutionary explanations of religion

includes both those that maintain there are benefits to religion, and

also those that "we may call the pearl theory: religion is

simply a beautiful by-product." By pearl theory, Dennet means that

"religion is not for anything, from the point of view of

biology; it doesn't benefit any gene, or individual, or group, or

cultural symbiont." This description appears to be almost the same as

what Gould and

Lewontin call a

spandrel.

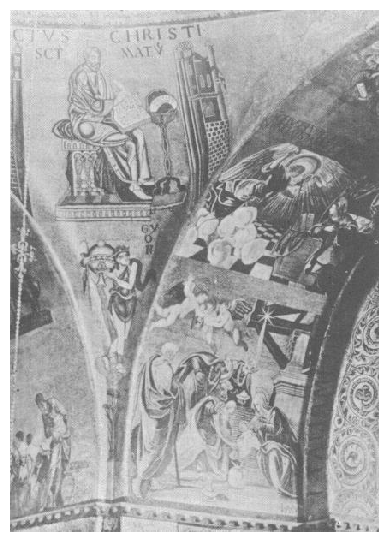

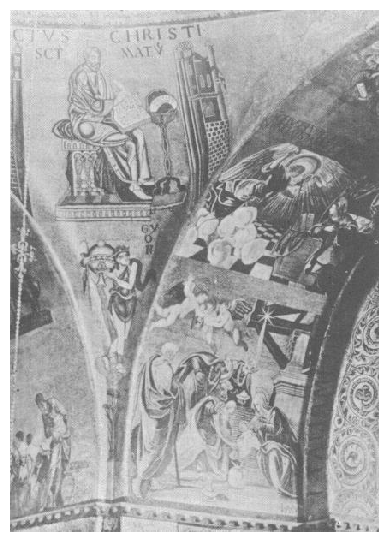

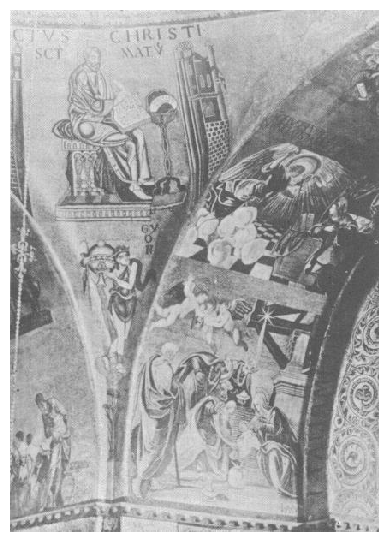

Figure 9.1:

The spandrel referred to by Gould and

Lewontin.

The word refers to the

tapering triangular surface region that occurs where the bases of arches

meet, notably in St Mark's Cathedral in Venice, where

they are exquisitely decorated with mosaics that exploit their

geometry. The spandrel might be thought

the reason for the surrounding architecture, but this would invert the

proper interpretation. The spandrel is a by-product of the overall

architectural design. It is then used opportunistically by the

mosaicists for their purposes193.

In evolution, argue

Gould and Lewontin, some things are not justified by an adaptationist

story, they are just opportunistic by-products. Incidentally, their

article exemplifies some penetrating criticism by biologists of

evolutionary explanations in anthropology and psychology (E.O.Wilson

being an author cited, and cannibalism the topic!). In fact their

criticism is precisely of the position adopted by Dennett's "we know

of no exceptions". Their whole point is that there are

exceptions. I am tempted to speculate that inventing a new metaphor

(pearl) rather than adopting the one already in common currency

(spandrel) is motivated by Dennett's realization of this fact, and his

desire to avoid promoting the ideas of two of the strongest critics of

sociobiology and evolutionary psychology: Gould and Lewontin.

Returning to the evolutionary explanation of religion, at times it seems

that Dennett is going to settle for the pearl/spandrel

theory, seeing

religion as a result of "our overactive disposition to look for

agents"194. But it serves his approach

better to remain non-committal and follow a speculative and eclectic

narrative pathway that allows different (and sometimes incompatible)

stories to serve for different phenomena.

Dennett's ideas and those of E. O. Wilson and Pinker, which he freely

draws from, have been directly subjected to withering criticism from

many quarters. The more pertinent of these criticisms have come not

from religious advocates, but from atheists and agnostics. Perhaps the

most telling are from evolutionary biologists, such as Richard

Lewontin and

H. Allen Orr, from experts in cognitive psychology and

computational linguistics such as Stephen Chorover and Robert Berwick,

and from philosophers of science such as Philip Kitcher195.

Pinker attributes this criticism to left-wing ideology,196

which he dates to the strong repudiation (in 1975) of Wilson's

book

Sociobiology in a review by 17 authors, including five

Harvard professors197.

But the more plausible reading is the one given originally in the critiques

and re-expressed in a response to Pinker:

"To us Darwinian fundamentalism is a form of irrationalism that, left

un-checked, erodes the very theory of evolution it embraces."198

Experts who understand evolution, psychology, and the philosophy of

science quite well, and who see the weakness of applying simplistic

adaptationist arguments to society and religion don't want biology to

be tarnished by the association.

It would not be very interesting go into greater detail and rebut the

individual assertions that Dennett makes, or to dissect the logical

argument, in so far as there is one. What I have been trying to do,

though, is to draw attention to the all-pervasive scientism that

informs his position. I see no reason to deny there is such a thing

as human nature, or that human nature has been influenced by

biological evolution as well as cultural evolution (meaning cultural

development). It is not that discussing religion (or music, or

anything else for that matter) from a scientific, or even a

specifically evolutionary, perspective is improper or

out-of-bounds. Rather, the fallacy is to imply that by doing so one is

discovering their real explanation, the scientific facts

that render superfluous all other descriptions, that debunk

other claims of significance or knowledge.

Actually it is even worse than that, and this is a feature of

evolutionary argument that, I must admit, drives this physicist

crazy. When Dennett says "The only honest way to defend" an

explanation of religion in terms of God's actions is to consider

"alternative theories of the persistence and popularity of religion

and rule them out"199, he is privileging

so-called scientific explanation to the extent that in order to

displace non-scientific explanation, even in non-scientific fields, it

only has to meet the standard of not being ruled out. Since

when has not being ruled out been enough to sustain a theory in

science - or in any other discipline? This astonishingly lowered

standard of what will count as a sufficient scientific demonstration

and explanation is one reason for the low esteem in the natural

science community, and elsewhere, of the specific theories of

evolutionary psychology. Not only that, but since music is in fact

well explained to the satisfaction of its professionals in ways that

actually provide useful predictive knowledge but are expressed in

non-scientific, musical terms, would it not be folly to discard those

explanations in favor of a scientific analysis of music? If so, why

would one think this way for religion? On what basis does it make

sense to rule inadmissible religious explanation of the things of

religion, and prefer a list of alternative, unsupported, speculative,

possible, `scientific' explanations? Only on the basis of

scientism.

Figure 9.1:

The spandrel referred to by Gould and

Lewontin.

The word refers to the

tapering triangular surface region that occurs where the bases of arches

meet, notably in St Mark's Cathedral in Venice, where

they are exquisitely decorated with mosaics that exploit their

geometry. The spandrel might be thought

the reason for the surrounding architecture, but this would invert the

proper interpretation. The spandrel is a by-product of the overall

architectural design. It is then used opportunistically by the

mosaicists for their purposes193.

In evolution, argue

Gould and Lewontin, some things are not justified by an adaptationist

story, they are just opportunistic by-products. Incidentally, their

article exemplifies some penetrating criticism by biologists of

evolutionary explanations in anthropology and psychology (E.O.Wilson

being an author cited, and cannibalism the topic!). In fact their

criticism is precisely of the position adopted by Dennett's "we know

of no exceptions". Their whole point is that there are

exceptions. I am tempted to speculate that inventing a new metaphor

(pearl) rather than adopting the one already in common currency

(spandrel) is motivated by Dennett's realization of this fact, and his

desire to avoid promoting the ideas of two of the strongest critics of

sociobiology and evolutionary psychology: Gould and Lewontin.

Returning to the evolutionary explanation of religion, at times it seems

that Dennett is going to settle for the pearl/spandrel

theory, seeing

religion as a result of "our overactive disposition to look for

agents"194. But it serves his approach

better to remain non-committal and follow a speculative and eclectic

narrative pathway that allows different (and sometimes incompatible)

stories to serve for different phenomena.

Dennett's ideas and those of E. O. Wilson and Pinker, which he freely

draws from, have been directly subjected to withering criticism from

many quarters. The more pertinent of these criticisms have come not

from religious advocates, but from atheists and agnostics. Perhaps the

most telling are from evolutionary biologists, such as Richard

Lewontin and

H. Allen Orr, from experts in cognitive psychology and

computational linguistics such as Stephen Chorover and Robert Berwick,

and from philosophers of science such as Philip Kitcher195.

Pinker attributes this criticism to left-wing ideology,196

which he dates to the strong repudiation (in 1975) of Wilson's

book

Sociobiology in a review by 17 authors, including five

Harvard professors197.

But the more plausible reading is the one given originally in the critiques

and re-expressed in a response to Pinker:

"To us Darwinian fundamentalism is a form of irrationalism that, left

un-checked, erodes the very theory of evolution it embraces."198

Experts who understand evolution, psychology, and the philosophy of

science quite well, and who see the weakness of applying simplistic

adaptationist arguments to society and religion don't want biology to

be tarnished by the association.

It would not be very interesting go into greater detail and rebut the

individual assertions that Dennett makes, or to dissect the logical

argument, in so far as there is one. What I have been trying to do,

though, is to draw attention to the all-pervasive scientism that

informs his position. I see no reason to deny there is such a thing

as human nature, or that human nature has been influenced by

biological evolution as well as cultural evolution (meaning cultural

development). It is not that discussing religion (or music, or

anything else for that matter) from a scientific, or even a

specifically evolutionary, perspective is improper or

out-of-bounds. Rather, the fallacy is to imply that by doing so one is

discovering their real explanation, the scientific facts

that render superfluous all other descriptions, that debunk

other claims of significance or knowledge.

Actually it is even worse than that, and this is a feature of

evolutionary argument that, I must admit, drives this physicist

crazy. When Dennett says "The only honest way to defend" an

explanation of religion in terms of God's actions is to consider

"alternative theories of the persistence and popularity of religion

and rule them out"199, he is privileging

so-called scientific explanation to the extent that in order to

displace non-scientific explanation, even in non-scientific fields, it

only has to meet the standard of not being ruled out. Since

when has not being ruled out been enough to sustain a theory in

science - or in any other discipline? This astonishingly lowered

standard of what will count as a sufficient scientific demonstration

and explanation is one reason for the low esteem in the natural

science community, and elsewhere, of the specific theories of

evolutionary psychology. Not only that, but since music is in fact

well explained to the satisfaction of its professionals in ways that

actually provide useful predictive knowledge but are expressed in

non-scientific, musical terms, would it not be folly to discard those

explanations in favor of a scientific analysis of music? If so, why

would one think this way for religion? On what basis does it make

sense to rule inadmissible religious explanation of the things of

religion, and prefer a list of alternative, unsupported, speculative,

possible, `scientific' explanations? Only on the basis of

scientism.

Summarizing the Militant Atheist Arguments

The popular militant atheist writers of this

century spend a great deal of effort to retell anti-religious

arguments which have a long history, dating from the nineteenth

century and in some cases much earlier. That is only natural. However,

the strong impression is given by writers that I've already cited and

others such as

Christopher Hitchens, and

Sam Harris, that there is new knowledge that

supports their arguments. It seems nearer the truth that there are

some new twists on the old arguments. It is worth trying to gather

them systematically, in the light of our discussion of scientism. In

broad strokes, the case made by the militant atheists consists of

three assertions: (1) God is a scientific hypothesis that has been

essentially disproved200 by science. (2) Evolution explains religion as nothing

more than a natural phenomenon. (3) Religion is demonstrably evil.

(1) The existence of God is, in my view, a factual question. Either

he exists or he doesn't. I see no reason to dispute

this. But insisting that God's existence is

a scientific question is a leap further that only scientism

justifies.

To identify factual with scientific - with knowledge gained through

the methods of the natural sciences - is the fallacy I am

addressing. It is so much a part of modern thought that even Michael

Polanyi falls into it in the midst of his systematic repudiation of

scientism. In his book Personal Knowledge, Polanyi's intent is

to describe knowledge as founded on personal commitment, more than a

supposed objectivity. He says "We owe our mental existence

predominantly to works of art, morality, religious worship, scientific

theory and other articulate systems which we accept as our dwelling

place and as the soil of our mental development. Objectivism has

totally falsified our conception of truth, by exalting what we can

know and prove, while covering up with ambiguous utterances all that

we know and cannot prove, even though the latter knowledge

underlies, and must ultimately set its seal to, all that we can

prove."201 This is an important thread

of Polanyi's argument. It is that scientific knowledge depends for its

existence upon much knowledge that is completely informal,

unspecified, and unscientific, for example our understanding of the

meaning of language. But Polanyi, most unhelpfully, identifies fact

and natural science, for example when saying

Ever since the attacks of philosophers like Bayle and Hume on the

credibility of miracles, rationalists have urged that the

acknowledgment of miracles must rest on the strength of factual

evidence. But actually, the contrary is true: if the conversion of

water into wine or the resuscitation of the dead could be

experimentally verified, this would strictly disprove their miraculous

nature. Indeed, to the extent to which any event can be established in

the terms of natural science, it belongs to the natural order of

things. However monstrous and surprising it may be, once it has been

fully established as an observable fact, the event ceases to be

supernatural. ...

Observation may supply us with rich clues for our belief in God; but

any scientifically convincing observation of God would turn religious

worship into an idolatrous adoration of a mere object, or natural

person.202

I completely concur with this important recognition that miracles, by

their very character, cannot be scientifically proved. The main reason

is that they are, practically by definition, not reproducible. If they

were reproducible, they would instead be part of natural science, as

Polanyi notes. But I find it most unhelpful and confusing when he implies

that resting on "factual evidence" is equivalent to being

"experimentally verified", or that being "established in the terms

of natural science" means the same as "established as an observable

fact". Polanyi wants to draw some fine distinctions: "The words

`God exists' are not, therefore, a statement of fact, such as `snow is

white', but an accreditive statement, such as ` "snow is white" is

true'... " And the way he sees it is that God exists but "not as a

fact - any more than truth, beauty, or justice exist as facts"203. Yet he immediately afterwards

tells us that religious conviction depends on factual evidence. I want

to be clearer than this. As far as I am concerned, there are

scientific facts, and there are non-scientific facts, such as facts of

history, jurisprudence, politics, personal acquaintance, and

religion. Just as science is not all the knowledge there is,

scientific facts are not all the facts there are. This is where I

contradict the presumptions of the atheists.

A crucial recent move of the militant atheists is the

argument that evolutionary explanations are intrinsically more

satisfactory than others because they explain the complex in terms of

the simple. Complex life is explained in terms of simpler chemical and

physical laws of nature. In contrast it is argued that explaining

anything in terms of God is to explain the simpler (things in the

world) in terms of the more complex (God). We've dispensed with

that argument in section 5.4.

(2) Explaining away religion as a natural phenomenon is not

new. Seeing religion as a product of human psychology is as old as

religion itself. Religions recognize the religious impulse as a

universal part of human nature. They have not regarded the

universality of spiritual yearning per se as a disproof of its

truthfulness; on the contrary, they argue that a universal religious

tendency is just what one might expect if God really

exists. Unbelievers doubtless have thought religion was merely

natural. Seeing religion as having developed over human history is a

similarly ancient understanding, and is similarly accommodated by most

faiths. For example, the Bible portrays God's self-revelation as

developing through a sequence of events of history. Explicitly

Darwinist explanations of religion are, practically speaking, as old

as Darwin, even though the Origin of Species was at pains to

avoid that hot issue. So there's nothing new in the idea that religion is

a universal part of human nature or in atheists arguing that

religion is nothing but a natural phenomenon. What is taken to be the

recent arguments' additional plausibility is based upon the `progress'

in evolutionary psychology and sociobiology in recent decades. I have

pointed out the controversial standing of these disciplines within the

science community.

For the most part, the arguments that

are offered to explain away religion are not scientific. We do not

require any evolutionary theory to tell us that humans can deceive

themselves, are prone to wishful thinking, exercise commitment to

ideas, or have heightened ability to detect agents. These traits might

lead to stubborn belief in the supernatural, which might be

mistaken. But the ideas surrounding them are not scientific. They are

pop-psychology to which is being attached a spurious honorific as if

they were derived from scientific analysis. Yet, trite as they are,

these are essentially the explanatory options that evolutionary

psychology supposes itself to have `discovered'. What's more, the

polemicists have no basis for making specific choices between the

options, so they leave them open. For their purposes, it does not

matter which of the dozens of different evolutionary explanations

might be correct. Provided we can be persuaded that some

natural explanation or combination of explanations is going to work,

their point is made. It does not matter to them whether the

explanation is of the type that variously sees religion as having

actual survival value for the group, or is of the type that sees it as

a by-product of some other trait with survival value for the

individual. The by-product theories include for example, "children

are native teleologists and many never grow out of

it"204, "Could irrational religion be

a by-product of the irrationality mechanisms that were originally

built into the brain by selection for falling in

love?"205, "irrationally strong

conviction is a guard against fickleness of mind", "hiding the truth

from the conscious mind the better to hide it from others", "a

tendency for humans consciously to see what they want to

see."206. And if these

biological-evolution explanations don't seem persuasive, one can

always fall back on the concept of

"memes", those hypothetical

entities which "evolve" as viruses of the mind, providing the aura

of scientific explanation to anthropological analysis of cargo cults,

for example, but working just as well or as poorly, as far as I can

see, for pretty much any fashion of the moment.

A truly scientific explanation ought to be different. It ought to be

uncomfortable with the myriad of possible explanations (with no way to

decide between them) not, like the polemicists, seemingly happy to

pile up more and more possibilities as if their multiplicity somehow

made the argument weightier. In any case, psychological analyses,

whether evolutionary or not, do not decide whether the content of the

beliefs analyzed is true. Dawkins might say that I believe in God

because I was taught to do so by my parents, or because it comforts me

to do so, or because I was programmed by evolution to do so. I might

say that Dawkins disbelieves because he was taught so by his parents,

or because it serves his desire for personal liberty to do so, or

because he was programmed to disbelieve by evolution. The arguments on

both sides are, I suppose, as convincing or unconvincing as one

another, but they don't settle the question of whether God exists one

way or the other. That's quite apart from the self-defeating logical

status of psychological determinism. If one supposes that the ideas

humans have are fully explained by a physical analysis of the brain,

or by a behaviorist analysis of training, or an evolutionist

description of inherited predispositions, or some combination of these

or other `scientific' analyses, then presumably the very belief that

this is the case is determined just by these influences. If that were

so, then why should we suppose the content of the belief to be true? In

short, if our beliefs are determined by evolution or psychology, why

should one believe so?

(3) The assertion that

religion is evil is not really part of the

scientism discussion, but for completeness I offer a few observations.

The fact that religious organizations and individuals do evil is amply

demonstrated by history.

1

1 1

1 2 1

1 3 3 1

1 4 6 4 1

1 5 10 10 5 1

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 9.2: Pascal's Triangle. It is a table whose nth row

contains the coefficients of algebra's "binomial expansion" of

(x+y)n. Each entry is the sum of the adjacent values of the row

above. The number of rows is unlimited.

Blaize Pascal, a convinced and earnest

Christian, as well as a remarkable mathematician and scientist, said

it in the mid seventeenth century "Men never do evil so completely

and cheerfully as when they do it from religious

conviction."207 What Pascal recognized was, first,

the simple point that people do evil intending and thinking that they

do good when they do it from conviction. Second is the more complex

point, that religious conviction has no monopoly on truth, yet is

conviction's strongest form. In

Steven

Weinberg's memorable atheist aphorism, the claim becomes "With or

without it, you'd have good people doing good things and evil people

doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, it takes

religion." Weinberg's punch line is either patently false, since

obviously many non-religious people who are otherwise `good' do evil

things, or else, if we charitably seek a serious meaning for the

aphorism, it is an extrapolation of Pascal to the point of asserting

that people do evil they take to be good only by religious

conviction. But even that is false unless you remove the word

religious, and say "only by conviction". The convictions that have

led people to what one might term `principled evil' have almost all

not been religious during the past couple of hundred

years. Realizing that, one is left only with the practically

tautological first part of the meaning of Pascal's pensée: people do

evil they take to be good only by conviction.

When it comes to assessing how good is the track record of

Christianity in its influence on society and history, it is not enough

simply to point to the evil that it may have inspired, demanded, or

permitted. One must ask, how good compared to what? From this

perspective, the recent militant atheist writings betray

themselves. They recount the now familiar list of evils of religion,

but largely ignore the evils of the atheist alternatives, which in the

twentieth century have inflicted suffering and death on an

unprecedented scale. By the simple measure of executions, for example,

atheist regimes have already outstripped the body-count of

Christianity for its entire history by an enormous factor208. Perhaps sensing the weakness of their position on

this score, the militant atheists try to minimize the extent to which

religion inspires good, and maximize its responsibility for

evil. Mother Teresa is scurrilously attacked by Christopher Hitchens,

and if Dawkins is to be believed, Martin Luther King's "religion was

incidental"209. They argue "Individual atheists may do evil

things but they don't do evil things in the name of

atheism. ... Religious wars really are fought in the name of religion,

and they have been horribly frequent in history. I cannot think of any

war that has been fought in the name of

atheism."210 This is double-think,

which can immediately be refuted. No war has ever been fought in the

name of generic `religion' or `theism'. Wars have been fought in the

name of specific religious beliefs and groups. Similarly no war has

ever been fought in the name of a generic `areligion' or

`atheism'. But many have been fought in the name of specific atheistic

beliefs and groups. The atheists' argument is: when religious people

do good, their religion is incidental, but when they do evil, their

religion is to blame; when atheists do good it is because they are

enlightened, but when atheists do evil, they do it as individuals, and

their atheism is not to blame, or if it looks as if they are motivated

by shared conviction, then this conviction is a kind of `religion', so

religion is (still) to blame. The inconsistency and special-pleading

is palpable.211

9.2 Rocks of Ages: A niche for religion

One of the better-known attempts at a kind of reconciliation of

science and faith of the past decade or two comes from a person active on the

evolutionist side of the school textbook debate, Stephen Jay Gould. In

his (1999) Rocks of Ages Gould puts forward

his "central principle of respectful noninterference ... the Principle

of NOMA, or Non-Overlapping Magisteria"212.

He summarizes this simple approach by saying "Science tries to

document the factual character of the natural world, and to develop

theories that coordinate and explain these facts. Religion, on the

other hand, operates in the equally important, but utterly different,

realm of human purposes, meanings, and values - subjects that the

factual domain of science might illuminate, but can never

resolve."

Gould cites the example of Thomas Burnet (1635-1715) whose The

Sacred Theory of the Earth is now dismissed as trying "to reimpose

the unquestionable dogmas of scriptural authority upon the new paths

of honest science". Incidentally, this is the same Burnet who played

a vital role in the accession of William of Orange to the English

throne and whose History of his own time served as one of the

major sources for Macaulay's History of England since the

accession of James the second, which I've cited earlier. Gould

gives several examples from twentieth century textbooks of

unrestrained condemnations of Burnet's concordist approach to natural

history. The Sacred Theory is largely an attempt at

harmonization of the Bible with the science of the day. In Gould's

view Burnet was unfairly castigated because, though he practiced both

magisteria, he kept them separate.

Gould quotes from Burnet as saying

'Tis a dangerous thing to engage the authority of scripture in

disputes about the natural world in opposition to reason; lest time,

which brings all things to light, should discover that to be evidently

false which we had made scripture assert.213

Gould's fairness and scholarship are evident in many places, for

example his discussion of the

reasons for Darwin's loss of faith, largely as a reaction to the

problem of suffering, brought into sharp personal relief by the

untimely death of his daughter. But Gould's attempts to argue that

T.H.Huxley also practiced NOMA and is unfairly portrayed as being

anti-religious, ring hollow. Or perhaps rather, one should say

that they reveal the very limited qualities of what Gould allows as

religion. The shallowness of Gould's and Huxley's permissible form of

religion is epitomized by this quote from Huxley's letter to Kingsley,

saying that he is led

... to know that a deep sense of religion was compatible with the

entire absence of theology. Secondly, science and her methods gave

me a resting-place independent of authority and tradition. Thirdly,

love opened up to me a view of the sanctity of human nature, and

impressed me with a deep sense of responsibility ...

I may be quite wrong, and in that case I know I shall have to pay

the penalty for being wrong. But I can only say with Luther, "Gott

helfe mir, Ich kann nichts anders".214

What Huxley (and it becomes clear Gould too) values, then, is a "deep

sense of religion" totally devoid of doctrinal content, or indeed

apparently any factual content. The authority that remains is science and her

methods. Huxley's image of himself is the embattled hero,

standing, like Luther, before a modern-day Diet of Worms, willing to

sacrifice his immortal soul for what he believes. For all the ironic

oratory, Huxley as martyr is not exactly a convincing

portrait. Though perhaps it is more convincing than the

similar self-portraits of the militant atheists of the early

twenty-first century.

For Gould the second magisterium seems to consist of matters of

value. He says that it is "dedicated to a quest for consensus, or at

least a clarification of assumptions and criteria, about ethical

`ought', rather than search for any factual `is'..." and includes

"much of philosophy, and part of literature and history" as well as

religion.

He rightly denies to science the ability to say anything about "the

morality of morals", citing as an example that the possible

anthropological discovery of adaptively beneficial characteristics of

infanticide, genocide, or xenophobia doesn't at all justify behaving in

that manner.

Gould is at his best when supporting the idea of NOMA by deflating the

excessive portrayal of warfare between science and religion. He

summarizes the arguments of Mario Biagioli215

to the effect that the Galileo

affair was more a matter of court intrigue than intellectual

contest.

And he discusses the openness of the Roman church to evolution, as

represented by Popes Pius XII (Humani Generis, 1950), and John

Paul II (1996). He devotes substantial space to critiques of Andrew

Dickson White's famous "History of the warfare between science and

theology in Christendom"216 (1896) and of the similar "History of the

conflict between religion and science" by John William Draper (1874)

and some of the political background of their times.

The flat-earth myth - that the church taught that the earth was flat,

and had to recant when Columbus proved otherwise - is delightfully

exploded. As shown by J.B.Russell Inventing the flat earth

(Prager, 1991) this fairy tale can be proved fictitious by documentary

evidence. The earth's sphericity was known from Greek antiquity and

promulgated throughout the middle ages by the Venerable Bede, Roger

Bacon, Thomas Aquinas, and others, who represented the cosmological

orthodoxy within Christianity, not the rare enlightened

individual. History texts prior to 1870 rarely mention the flat-earth

myth, while almost all those after 1880 do. It is not a coincidence

then, that the flat-earth myth gains its currency at just about the

time of the warfare advocates, and that both White and Draper cite it as a

prime example of warfare.

Gould points out that

the celebrated exchange between Bishop Wilberforce and T.H.Huxley on

the descent of man took place at an 1860 meeting of the British Association

whose formal paper was an address by the same Draper on the

"intellectual development of Europe considered with reference to the

views of Mr. Darwin". In other words, it arose not in the context of a

scientific debate, but following an early discussion of "social

Darwinism".

Gould cites with approval the physiologist J.S.Haldane, whom he calls

a "deeply religious man", in whose Gifford Lectures for 1927 a most

telling phrase appears "If my reasoning has been correct, there is no

real connection between religion and the belief in supernatural events

of any sort or kind".

This is the religion that Gould has in mind as the candidate for NOMA,

because he says "... NOMA does preclude the additional claim that

such a God must arrange the facts of nature in a certain set and

predetermined way. For example, if you believe that an adequately

loving God must show his hand by peppering nature with palpable

miracles, ... then a particular, partisan (and minority) view of

religion has transgressed in the magisterium of science

..."217

The creationism and evolution textbook debate is one

in which Gould was directly involved. Two important general points

that he makes are that

there is probably a majority of clergy (as well as scientists) against

imposition of specific theological doctrine on the science curricula

of public schools; and that the controversy is a remarkably American

phenomenon. "No other Western nation faces such an incubus as a

serious political movement".

He attributes the latter predominantly to America's "uniquely rich

range of sects". I think there may be more cogent reasons218. Gould's

recounting of the Scopes trial of 1925 is interesting in

focusing on the difference between the reality and the 1955 cinematic

version of Inherit the Wind, not to mention the polemic of

H.L.Mencken. Both the Dayton creationists and their opponents, the

ACLU, were looking forward to a guilty verdict so that the case

could move on to higher courts where the real issues of

constitutionality were to be fought. The conviction was overturned on

the technicality that the judge had no authority to impose the fine of

$100 (exceeding his limit of $50) and although this is portrayed by

evolutionists as a victory, it was more like a defeat for both sides,

since it prevented the real issues from being joined.

Gould also writes passionately about

William Jennings Bryan, the famous creationist prosecutor of the

Scopes trial, recalling that, far from being by nature a benighted

traditionalist, he was, for his whole political career, a liberal and

progressive reformer. Gould attributes Bryan's uncharacteristic

position to his misunderstanding.

Bryan's

attitude to evolution rested upon a three-fold error. First, he made

the common mistake of confusing the fact of evolution with the

Darwinian explanation of its mechanism. He then misinterpreted natural

selection as a martial theory of survival by battle and destruction of

enemies. Finally, he fell into the logical error of arguing that

Darwinism implied the moral virtuousness of such deathly

struggle.219

While acknowledging that Bryan was in part responding to the misuse of

Darwinism by scientists and their acolytes, he concludes that

"The originator of an idea [Darwin] cannot be held responsible for egregious

misuse of his theory"

I take Gould's intentions in advocating what he calls NOMA to

be entirely constructive. He undoubtedly has an agenda to defend the

independence of science. But there seems no reason to doubt his

genuine concern to find a place in intellectual thought for morality

and value. He associates these (though not uniquely) with religious

underpinnings, rather than with any vain attempts to derive ethics

from science or natural history.

Gould's NOMA principle has been much criticized. As we've seen, it

does not satisfy the militant atheists, of course, but it also does

not satisfy militant, or even tolerably robust, theists. The weakness

of Gould's position is primarily that it is scientistic. When he

identifies the magisterium of science as "our drive to understand the

factual character of nature" he is saying that facts are discovered

by science (alone), or in other words that the only real knowledge is

scientific. Undoubtedly Gould wishes to set up a contrast between

facts (science) and values (religion). The problem with this common

opposition is that values are not the natural disjoint of facts. The

plain converse of the view that facts are the domain of science

is that the domain of religion is feelings, or worse still

fantasy. Gould does not mean that converse (I think), and intends to

express respect for religion; but he can't avoid the implication. To

be fair, he does qualify the "facts" by the phrase "of nature",

and were it not for the rest of his exposition, that might leave open

the possibility of there being facts "of something else". But he

never refers to the domain of religion as being a question of

knowledge or fact. The religion that he is making room for is a

religion empty of any claims to historical or scientific fact,

doctrinal authority, and supernatural experience. Such a religion,

whatever may be its attractions to the liberal scientistic mind, could

never be Christianity, or for that matter, Judaism or Islam.

For all of his justified critical

analysis of Andrew Dickson White's polemic of 100 years earlier, and

for all that he aspires to a more balanced interpretation of history,

the logic of Gould's position is therefore scarcely different from

White's. White was at pains to say that science's warfare was

not with religion but with "theology". By this, as he clearly

stated in his introduction, White meant distinctive religious

doctrines that he called sectarian, but which might more descriptively

be called confessional or foundational. In White's portrayal,

religion's claims to knowledge or authoritative teaching are what

science is disputing. For White, and for Gould, there is room for a

vague religiosity which serves useful purposes as a civic religion and

as an emotional source of moral authority. Both men welcome, and even

promote, that religiosity. But neither has left room for anything that

looks like orthodox Christianity, based on unique events two thousand

years ago: the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth.

9.3 Behind the mythology

Science and Christianity have had a lot of interactions during and

since the Scientific Revolution, but none has become so iconic as that

of

Galileo and the Roman Catholic church.

Figure 9.3: Galileo before the Inquisition, Cristiano Banti, oil on

canvas.

The popular image of this confrontation is wonderfully captured in the

painting by Cristiano Banti, Figure 9.3220.

Galileo stands

in a heroic pose, his head set-off by what almost seems a halo of

light behind it. His interrogators have their backs to the wall

literally as well as figuratively. The unhappy faces of the passive

inquisitors, one of which is partly shrouded by a hood, are averted

from the brightness of Galileo's face. The central accuser leans

forward to confront Galileo, pointing to an open scroll, next to which

stands a quill and ink. He is commanding Galileo to sign a confession

or a recantation.

The plain wall is bright behind them, with only the legs of a crucifix

visible. It seems almost as if the brightness has come directly from

Galileo's saintly head, metaphorically illuminating the darkness of

the nether regions and benighted religious with the breaking light of science.

Of course this portrait deliberately sets out to make a statement and

to promote a viewpoint: that Galileo was an early martyr and hero in

the long war between science and Christian faith. What is really

interesting about it, though, is not so much its portrayal, as its

date: 1857. This is the image of Galileo that was promoted in the

mid-nineteenth century, more than two hundred years after the events.

Almost all the empirical philosophers of the Scientific Revolution in

the seventeenth century soon did adopt the heliocentric model of the

solar system, in whose defense Galileo had fallen

into papal disfavor. But even those who were Galileo's friends and

admirers could hardly have seen the events of the confrontation in the

way Banti paints them. Galileo's scientific evidence was weak, and

some of his theories were plain wrong. He had been allowed remarkable

latitude, in those troubled times, to pursue his science, provided he

kept out of theology and Bible interpretation. The pope himself had

been his friend and encourager. But Galileo had drained all this

good-will, enraged his enemies, and alienated most of his powerful

friends by publishing through what seemed like subterfuge an arrogant

populist imagined dialogue promoting his ideas and portraying their

opponent as `Simplicio', the Simpleton. Both the heliocentric solar

system and also Galileo's approach to scriptural interpretation are

now commonplace inside and outside the Roman church. And by 1857 one

could see that these and other key contributions had been fully

vindicated. Yet in his time, Galileo did not heroically stand on

principle embodying the light of science before the ignorant

Inquisition; the frightened old man would do whatever he had to do to

preserve his life and comfort. One should not blame him for

that. Besides, he remained a good Catholic, and so far as we can tell

had not been seeking to alienate the church, or to undermine its

authority, except in so far as it was represented by the schoolmen.

So, to summarize, Banti's painting is revealing not of the events or

the spirit of the seventeenth century, but of the attitudes towards

science, and the scientism, of the mid-nineteenth.

There had not, in the minds of most scientists, been an entrenched

warfare or even much of an ongoing intellectual confrontation between

science and Christianity in the intervening centuries. But it served

the purposes of many academics to persuade themselves that there had

been.

Andrew Dickson White was just

beginning his campaign with Ezra Cornell to found a new model of

university. They considered the influence of what they called

sectarian religion to be detrimental to learning and to society; so

their intention was to spearhead a new movement of essentially secular

education, in place of the Christian universities which still

dominated academia. Cornell University was to be an institution in

which religious doctrine was to have no place221. The content of the pamphlets and articles

that were his propaganda in support of this campaign eventually became

White's famous book The warfare of science with theology in

christendom (1896).

In it he gathered and recounted numerous

historical examples of areas in which the growth of what he called

science encroached upon traditionally religious intellectual

territory. Each development is portrayed as initially meeting with

stubborn resistance from the entrenched theological power structures,

but eventually from sheer force of evidence and argument overthrowing

that resistance and moving forward into greater knowledge and

enlightenment. The theme is repeated over and over in this long and

eventually tedious book, but it lends itself to stirring melodrama,

complete with martyrs, heroes and villains; intrigues and battles; and

all the elements that go to make a good story.

White, like many of his contemporaries, used the word science with an

enormously wide meaning; so that it encompassed the entirety of

liberal scholarship. In addition to astronomy, chemistry, geology and

the other natural sciences, his book has chapters on Egyptology and

Assyriology, philology, comparative mythology, economics, and biblical

criticism, referring to all as science, and implying that the

intellectual methodologies of all are similar.

This book, and presumably the pamphlets before it, captured the

imaginations of many of the academics of the day and its thesis

gradually became accepted even by many Christians as representing a

fact of history that science and theology were perpetually at war. For

academics, who at that stage almost universally regarded science as

the guiding example of all rational thought, it meant so much the

worse for religion. For Christians whose faith ruled their lives, it

meant, by contrast, so much the worse for science. And thus the

warfare metaphor as it was gradually accepted by both sides became a

self-fulfilling prophecy.

The relationship of science and Christianity in the three centuries

prior to this transition had been complicated, and sometimes

tense. But the men who pushed forward the growing knowledge of nature,

during that period, were more often pious believers than they were

outspoken infidels or scientistic secularists. The universities were

of course Christian foundations, Oxford and Cambridge required their

ordinary college fellows to be ordained if they remained beyond a

limited tenure.

Figure 9.3: Galileo before the Inquisition, Cristiano Banti, oil on

canvas.

The popular image of this confrontation is wonderfully captured in the

painting by Cristiano Banti, Figure 9.3220.

Galileo stands

in a heroic pose, his head set-off by what almost seems a halo of

light behind it. His interrogators have their backs to the wall

literally as well as figuratively. The unhappy faces of the passive

inquisitors, one of which is partly shrouded by a hood, are averted

from the brightness of Galileo's face. The central accuser leans

forward to confront Galileo, pointing to an open scroll, next to which

stands a quill and ink. He is commanding Galileo to sign a confession

or a recantation.

The plain wall is bright behind them, with only the legs of a crucifix

visible. It seems almost as if the brightness has come directly from

Galileo's saintly head, metaphorically illuminating the darkness of

the nether regions and benighted religious with the breaking light of science.

Of course this portrait deliberately sets out to make a statement and

to promote a viewpoint: that Galileo was an early martyr and hero in

the long war between science and Christian faith. What is really

interesting about it, though, is not so much its portrayal, as its

date: 1857. This is the image of Galileo that was promoted in the

mid-nineteenth century, more than two hundred years after the events.

Almost all the empirical philosophers of the Scientific Revolution in

the seventeenth century soon did adopt the heliocentric model of the

solar system, in whose defense Galileo had fallen

into papal disfavor. But even those who were Galileo's friends and

admirers could hardly have seen the events of the confrontation in the

way Banti paints them. Galileo's scientific evidence was weak, and

some of his theories were plain wrong. He had been allowed remarkable

latitude, in those troubled times, to pursue his science, provided he

kept out of theology and Bible interpretation. The pope himself had

been his friend and encourager. But Galileo had drained all this

good-will, enraged his enemies, and alienated most of his powerful

friends by publishing through what seemed like subterfuge an arrogant

populist imagined dialogue promoting his ideas and portraying their

opponent as `Simplicio', the Simpleton. Both the heliocentric solar

system and also Galileo's approach to scriptural interpretation are

now commonplace inside and outside the Roman church. And by 1857 one

could see that these and other key contributions had been fully

vindicated. Yet in his time, Galileo did not heroically stand on

principle embodying the light of science before the ignorant

Inquisition; the frightened old man would do whatever he had to do to

preserve his life and comfort. One should not blame him for

that. Besides, he remained a good Catholic, and so far as we can tell

had not been seeking to alienate the church, or to undermine its

authority, except in so far as it was represented by the schoolmen.

So, to summarize, Banti's painting is revealing not of the events or

the spirit of the seventeenth century, but of the attitudes towards

science, and the scientism, of the mid-nineteenth.

There had not, in the minds of most scientists, been an entrenched