Chapter 1

Science and scientism

1.1 Introduction

Science is the most remarkable and powerful cultural artifact humankind

has ever created. What is more, most people in our society

regard science as providing us with knowledge about the natural world

that has an unsurpassed claim to reality and truth. That is one reason

why I am proud to be a physicist, a part of the scientific

enterprise. But increasingly I am dismayed that science is being

twisted into something other than what it truly is. It is portrayed as

identical to a philosophical doctrine that I call

`scientism'.

Scientism is the belief that all valid knowledge is

science. Scientism says, or at least implicitly assumes, that rational

knowledge is scientific, and everything else that claims the status of

knowledge is just superstition, irrationality, emotion, or nonsense.

The purpose of this book is to show the pervasiveness of the doctrine

of scientism; to explore its coherence, and consequences; and to show

that it must be repudiated, both to make sense of a vast range of

non-scientific human endeavor, and also for science itself. One of the

conflicts that is most visible in current culture is between scientism

and religion. But the overall confrontation is not just with religious

faith, prominent though that part of the debate may be. Religious

belief is not at all unique in being an unscientific knowledge. On the

contrary, I shall argue that there are many important beliefs, secular

as well as religious, which are justified and rational, but not

scientific. And if that is so, then scientism is a ghastly

intellectual mistake.

But how could it have come about that this mistake is so widespread,

if it is a mistake? The underlying reason is that scientism is

confused with science. This confusion is commonplace in many, many

popularizations of science. Scientists of considerable reputation

speak with authority and understanding (but rarely modesty) about the

knowledge and technology that science has brought; and frequently they

introduce into their explanations, without acknowledging it,

non-scientific assumptions, unjustified extrapolations, philosophy and

metaphysics either based on or promoting scientism. It is natural

then, for readers, particularly those without inside knowledge of

science, to assume that science and scientism are one and the

same. After all, many leading scientists, and science popularizers,

speak and act as if they are. A major strand within the community of

science thus directly promotes this confusion.

What is more, several major strands within the community of religious

faith also promote this confusion. On the conservative theological

wing, which feels itself in an intellectual battle with a secular

academy, there is a deep suspicion of science because it is seen as a

countervailing authority against religious orthodoxy. Most of the

theologically liberal wing, in contrast, long ago adopted scientism,

because they confused it with science. But both sides, whether

rejecting or assimilating, have confused science and scientism; and

that confusion is a major factor in the stance they each take.

Broader non-science academic disciplines - and here I am thinking of

subjects such as

history, literature, social studies,

philosophy, and the arts - have related problems. I shall argue that

one can understand many of the trends of academic thought in the past

century or so as being motivated in part by either embracing or

rejecting scientism. Those trends that embrace scientism, do so

because they feel compelled by the intellectual stature of science:

they confuse the two. Those that (more recently) reject scientism,

seeing its sterility, seem often to reject science as well, because

they have confused the two.

Scientism is many-faceted. It is, first of all, a philosophy of

knowledge. It is an opinion about the way that knowledge can be

obtained and justified. My single sentence definition of scientism

focuses on this underlying and foundational aspect:

" Scientism is

the belief that all valid knowledge is science." However, the

repercussions of this viewpoint are so great that scientism rapidly

becomes much more. It becomes an all-encompassing world-view; a

perspective from which all of the questions of life are examined; a

grounding presupposition or set of presuppositions which provides the

framework by which the world is to be understood. Therefore, from

scientism spring many other influences on thought and behavior,

notably the principles that guide our understanding of meaning and

truth; the ethical and social understanding of who we are and how we

should live; and ultimately our answers to the `big questions': our

religious beliefs.

In so far as scientism is an overarching world-view, it is fair to

regard it as essentially a

religious

position. Its advocates are unhappy with such an assertion, and argue

that because scientism does not entail the belief in the supernatural,

and does not entail ceremonials and rituals, it cannot be regarded as

religion. But that is hair-splitting. There are religions that don't

involve a belief in God, and religions that don't require

participation in ceremonies. What's more, as we will see, several of

the historic forms that scientism has taken actually do involve

ceremonials and rituals of religious intent. In any case, the key

aspect of religious conviction that scientism shares with most

organized religions is that it offers a comprehensive principle or

belief, which itself cannot be proved (certainly not scientifically

proved) but which serves to organize our understanding and guide our

actions.

Higher education in the West, in its beginnings, was almost

exclusively a Christian undertaking. Its rationale and content were

dominated by the propagation of Christian truths and the education of

people to undertake that mission. As it grew, of course, much broader

perspectives were encompassed, but even well into the nineteenth

century, religious observance and education were dominant aspects of

most colleges and

universities. In the second half of that

century, though, a transformation occurred, away from religious to

more secular motivations and content.1 To a great extent, that transformation can be

viewed as a conversion to scientism. Not that all twentieth century

academics subscribed overtly to scientism. But just as Christian

presuppositions were a kind of academic

mental

habitat in earlier centuries, so, scientism became the de facto

world-view of the academy. Scientistic viewpoints had been advocated

by a vocal minority of intellectuals since the beginning of the

Enlightenment, and had gained increasing

dominance prior to this transformation. But after it, scientism became

practically the

orthodoxy of the academy.

In the later parts of this study, I will explore briefly some of the

more practical consequences of scientism in modern attitudes to

political and social decision making. One can consider the emphasis on

technological solutions for the challenges we face

as a facet of scientism. The modern reliance on technology to solve

all manner of social challenges was increasingly subject to critiques

from human and religious perspectives as the twentieth century wore

on. The belief in human `progress', based on technique, failed in the

face of the stark realities of world wars and gulags. But because the

underlying scientism was not displaced from its intellectual

dominance, the

technological

imperative and the reliance on the technological fix seem as strong as

ever.

Repudiation of scientism is the only way that we can break free from

some of the more debilitating habits of thought that have dominated

modern intellectual life. But this repudiation is unsustainable, even

by the most heroic effort, without a distinction between science and

scientism. If denying scientism's sway requires us to deny the

truthfulness, value, or reality of scientific knowledge - as seems to

be implied by some of today's critiques - then in my opinion the move

will fail. And it should fail, because in fact science does give real,

reliable, knowledge. It is just that science and scientism are not the

same thing. Science is not all the knowledge there is.

1.2 Science, what do we mean by it?

Perhaps, gentle reader, you are yourself already highly dubious about

the distinction that I am trying to draw. Quite possibly, you take the

view that science really is the only reliable route to knowledge: that

science is simply the systematic critical study of any field of

activity: that the word science simply describes

knowledge, which after all is its Latin

etymology. If so, then I need to convince you, first,

that there is something distinctive about the disciplines that we

traditionally call science, something that is different from other

disciplines; and second, that that distinctiveness calls for definite

characteristics of the things we study using the methods of science,

which not all questions possess. In other words, I must show both that

there are in fact functional definitions of science, and that not all

interesting knowledge falls within the scope of the definitions.

A major cause of confusion is that the word

science is used with at least two

meanings. Those meanings are completely different; confusing the two

has a natural tendency to lead to scientism. One meaning, which I

just alluded to, looks to the derivation of the word. It comes from

the Latin scientia which means simply knowledge. Based on this

foundation, the word science is sometimes used to describe any

systematic orderly study of a field of knowledge; or by extension the

knowledge that such study produces. The other meaning of the word

science is today a far more common usage. It is that "science"

refers to the study of the natural world.

The Encyclopédie and Samuel Johnson

2

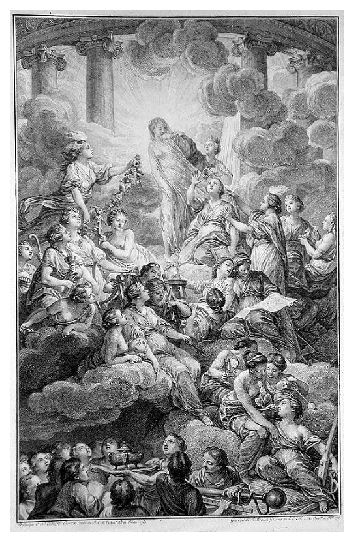

Figure 1.1: Frontispiece

of Diderot's Encyclopédie. Reason and

philosophy revealing truth. Drawn by Charles-Nicolas Cochin,

1764.

Prior to the nineteenth century, the word science was used, especially

in continental Europe, to mean simply knowledge. The

Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts

et des Métiers3 was edited by Denis

Diderot and published in 21 volumes of text and 11 of illustrative

plates during the years 1751 to 1777. It was in many ways the

embodiment of Enlightenment thinking. Its definition of the word

science is this:

Figure 1.1: Frontispiece

of Diderot's Encyclopédie. Reason and

philosophy revealing truth. Drawn by Charles-Nicolas Cochin,

1764.

Prior to the nineteenth century, the word science was used, especially

in continental Europe, to mean simply knowledge. The

Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts

et des Métiers3 was edited by Denis

Diderot and published in 21 volumes of text and 11 of illustrative

plates during the years 1751 to 1777. It was in many ways the

embodiment of Enlightenment thinking. Its definition of the word

science is this:

SCIENCE, as a

philosophical concept, means the clear and certain knowledge of

something, whether founded on self-evident principles, or via

systematic demonstration. The word science is, in this sense, the

opposite of doubt; opinion stands midway between science and doubt.

(The original was in French.) Clearly, by this definition, science is

no different from what we commonly simply call knowledge. If this

were all that the word science connoted, there would be no problem. We

would use "science" interchangeably with "knowledge" and little

else would be implied. But, of course, this is not the only

connotation in modern usage. Most of the time, today, when people

refer to science they are referring to

natural science, our

knowledge of nature, discovered by experiment and (most convincingly

mathematical) theory. This is the meaning I use.

The Encyclopédie itself reflects an ambiguity about the usage of the

word science, which may have been deliberate. The formal definition it

gives, is equivalent to "knowledge". But the Encyclopédie's usage

strongly implies the natural and technological knowledge

that is captured by the modern meaning, natural science.

Consider the title of the work itself, which might be translated,

"Encyclopedia or Reasoned Dictionary of

Sciences, Arts, and Trades". Lest the modern reader be misled by this

literalistic translation, we should recognize that the word Arts here

means predominantly what we would call technology. Here is part of the

Encyclopédie's own article on ART, which was evidently Diderot's

manifesto for the work.

Origin of the arts and sciences. In pursuit of his needs, luxury,

amusement, satisfaction of curiosity, or other objectives, man applied

his industriousness to the products of nature and thus created the

arts and sciences. The focal points of our different reflections have

been called "science" or "art" according to the nature of their

"formal" objects, to use the language of logic. If the object leads to

action, we give the name of "art" to the compendium of the rules

governing its use and to their technical order. If the object is

merely contemplated under different aspects, the compendium and

technical order of the observations concerning this object are called

"science."

Thus, for example, according to Diderot,

metaphysics is a science and

ethics

is an art. Theology is a science and pyrotechnics an art! So

arts are the products of applying industriousness to

nature, and differ from "science" in that arts are practical,

whereas science is contemplative. Moreover, for Diderot, there are

subdivisions of arts:

Division of the arts into liberal and mechanical arts. When men

examined the products of the arts, they realized that some were

primarily created by the mind, others by the hands. This is part of

the cause for the pre-eminence that some arts have been accorded over

others, and of the distinction between liberal and mechanical

arts.

Then after promoting the value of the mechanical arts and criticizing

those who disdain them, who by their prejudice "fill the cities with

useless spectators and with proud men engaged in idle speculation",

Diderot extols

Bacon and Colbert as champions of the

mechanical arts and says, "I shall devote most of my attention to the

mechanical arts, particularly because other authors have written

little about them."

The modern reader may be forgiven for feeling that Diderot has

multiplied distinctions in ways that are more confusing than

enlightening. Nevertheless, the main point is clear. The

Encyclopédie is a work predominantly about natural science and

technology. It defines the word science to mean knowledge in general;

but then it focuses on natural science and technology. Here we see

scientism in its youth. And even in its youth, it seems to be based on

deliberate confusion of language. The French

philosophes (whose champion Diderot was) and those

who followed them were quite deliberate in their attempt to undermine

confessional religious faith and any authority based on it. Their

avowed aim was to undermine the authority of the clergy and the

church; and hence the political system, the

Ancien Régime of which

clerical power was one foundation

stone. Those opposed to the monarchy and aristocracy used every

technique at their disposal from the satire of

Voltaire to the social activism of the

revolutionaries. But one of the most powerful of their techniques,

and arguably the most lasting legacy, was to insinuate scientism as an

unacknowledged presupposition into much of the intellectual climate of

the succeeding two centuries.

Samuel Johnson's dictionary4, or to give it its

full title, A DICTIONARY of the English Language: in which The

WORDS are deduced from their ORIGINALS, and ILLUSTRATED in their

DIFFERENT SIGNIFICATIONS by EXAMPLES from the best

WRITERS5 was

perhaps the most definitive work of English usage up to 1755, when it

was first published. It had far less of a deliberate agenda than the

Encyclopédie, and was a remarkable, nine-year, practically

solo effort, unlike the French dictionary of the day which took forty

scholars forty years. Johnson's boast, based on his initial optimistic

estimate of only a three-year schedule, was that this showed "As

three to sixteen hundred, so is the proportion of an Englishman to a

Frenchman"6.

The 11th edition, abstracted like some earlier editions by Johnson to

produce additional profit through a more accessible, less bulky

work, retains only the authors, not the texts

by which the meanings are illustrated and its definition of science

reads

Science. 1. Knowledge. Hammond. 2. Certainty grounded on

demonstration. Berkley. 3. Art attained by precepts, or built

upon principles. Dryden. 4. Any art or species of

knowledge. Hooker, Glanville. 5. One of the seven liberal arts, grammar,

rhetorick, logick, arithmetick, musick, geometry, astronomy. Pope.

Evidently this definition conforms to the more general concept as

addressing any systematic body of knowledge. Several

of the original quotations from which these definitions are derived do

show signs of preference towards natural science. Nevertheless, the

last definition, as liberal art, emphatically retains the breadth of

meaning that a classical derivation might imply.

Two Nineteenth Century Historians

Insight into the usage of the word science in the nineteenth century

can be gleaned from the writing of

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859), a lawyer,

politician, colonial administrator, poet, essayist and historian

7

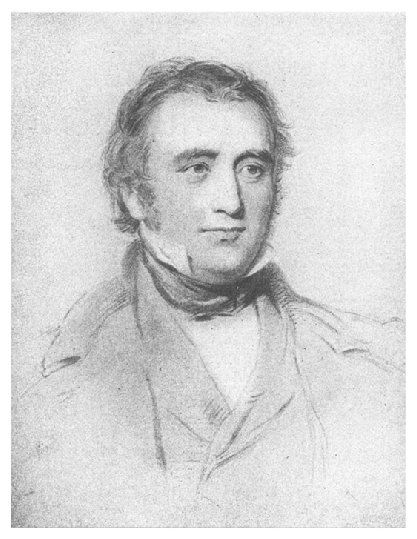

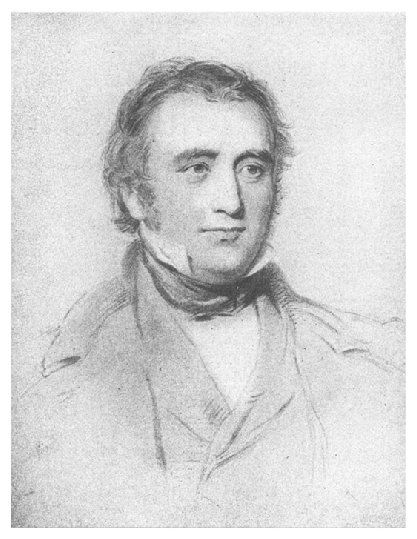

Figure 1.2: Thomas Babington Macaulay at age 49. After a drawing by

George Richmond.

Macaulay's

The History of

England from the accession of James the second was an immediate

bestseller when it was published in mid century (volumes 1 and 2 in

1848), and remains a classic of English literary style and popular

history, still in print. Macaulay's writing is considered also a

characteristic example of

`Whig History', which means an

interpretation of history in terms of the progressive growth of

liberty and enlightenment, accompanying the increase of democratic and

parliamentary power, as opposed to monarchy and aristocracy.

Macaulay, while unromantic in his perspicacious analysis of the

motivations of individuals and the sentiments of the populace, is fond

of sweeping assessments such as "From the time when the barbarians

overran the Western Empire to the time of the revival of letters, the

influence of the Church of Rome had been generally favorable to

science, to civilization, and to good government. But during the last

three centuries, to stunt the growth of the human mind has been her

chief object."8

We see in this quotation that Macaulay refers to science

as the intellectual component of the growth of the human mind, which,

along with civilization and government, constitutes the progress that

he is interested to document. Macaulay's usage of

`science' here is very broad, encompassing all of

liberal studies, not just natural science. Yet later in his overview

of England in 1685, speaking about historical assessments of the size

of the English population (about five million), he writes "Lastly, in

our own days Mr. Finlaison, an actuary of eminent skill, subjected the

ancient parochial registers of baptisms, marriages, and burials to all

the tests which the modern improvements in statistical science enabled

him to apply."9

So `science' is a natural description of mathematical analysis. But in

discussing the low relative degree of militarization of England he

says "... the defence of nations had become a science and a calling"

meaning that the army was becoming professionalized, and associated

with systematic learning, though not necessarily that of natural

philosophy.10

Macaulay speaks of the far more effective naval officers of that day

who had risen through the ranks rather than acquiring their

appointment, as did the `gentlemen captains', by political

preferment. "But to a landsman these tarpaulins, as they were called,

seemed a strange and half-savage race. All their knowledge was

professional; and their professional knowledge was practical rather

than scientific."11

So here he is reflecting the

Encyclopédie's distinction between art: the practical; and

science: the contemplative, or perhaps in modern terminology

theoretical.

Macaulay sees science as preeminently the result of

formal education, but later refers to the distinguishing of right from wrong

as part of "ethical science" (i.e. the science of ethics).

Thus the usage of Macaulay reflects an understanding of science as

knowledge that is

contemplative and

formally-learnt, encompassing the broad scope of human endeavor, yet

only somewhat ambiguously focused on situations and methods that are

predominantly the province of natural and mathematical studies. That

ambiguity, though, is in practice dispelled by his summary under the

heading "State of science in England" in 1685. Noting the

foundation, just twenty five years before, of the

Royal Society (whose concerns surely serve as an

indisputable definition of science as natural philosophy), he lists

the subjects of his state of science as including agricultural reform,

medicine, sanitation, " ... the chemical discoveries of

Boyle, and

the earliest botanical researches of Sloane. It was then that Ray made

a new classification of birds and fishes, and that the attention of

Woodward was first drawn toward fossils and shells. ... John Wallis

placed the whole system of statics on a new foundation. Edmund Halley

investigated the properties of the atmosphere, the ebb and flow of the

sea, the laws of magnetism, and the course of the comets; ... mapped

the constellations of the southern

hemisphere"

12.

With the sole

possible exception of Petty's "Political Arithmetic", an early

treatise in economic statistics, what Macaulay refers to are topics in

natural science.

Figure 1.2: Thomas Babington Macaulay at age 49. After a drawing by

George Richmond.

Macaulay's

The History of

England from the accession of James the second was an immediate

bestseller when it was published in mid century (volumes 1 and 2 in

1848), and remains a classic of English literary style and popular

history, still in print. Macaulay's writing is considered also a

characteristic example of

`Whig History', which means an

interpretation of history in terms of the progressive growth of

liberty and enlightenment, accompanying the increase of democratic and

parliamentary power, as opposed to monarchy and aristocracy.

Macaulay, while unromantic in his perspicacious analysis of the

motivations of individuals and the sentiments of the populace, is fond

of sweeping assessments such as "From the time when the barbarians

overran the Western Empire to the time of the revival of letters, the

influence of the Church of Rome had been generally favorable to

science, to civilization, and to good government. But during the last

three centuries, to stunt the growth of the human mind has been her

chief object."8

We see in this quotation that Macaulay refers to science

as the intellectual component of the growth of the human mind, which,

along with civilization and government, constitutes the progress that

he is interested to document. Macaulay's usage of

`science' here is very broad, encompassing all of

liberal studies, not just natural science. Yet later in his overview

of England in 1685, speaking about historical assessments of the size

of the English population (about five million), he writes "Lastly, in

our own days Mr. Finlaison, an actuary of eminent skill, subjected the

ancient parochial registers of baptisms, marriages, and burials to all

the tests which the modern improvements in statistical science enabled

him to apply."9

So `science' is a natural description of mathematical analysis. But in

discussing the low relative degree of militarization of England he

says "... the defence of nations had become a science and a calling"

meaning that the army was becoming professionalized, and associated

with systematic learning, though not necessarily that of natural

philosophy.10

Macaulay speaks of the far more effective naval officers of that day

who had risen through the ranks rather than acquiring their

appointment, as did the `gentlemen captains', by political

preferment. "But to a landsman these tarpaulins, as they were called,

seemed a strange and half-savage race. All their knowledge was

professional; and their professional knowledge was practical rather

than scientific."11

So here he is reflecting the

Encyclopédie's distinction between art: the practical; and

science: the contemplative, or perhaps in modern terminology

theoretical.

Macaulay sees science as preeminently the result of

formal education, but later refers to the distinguishing of right from wrong

as part of "ethical science" (i.e. the science of ethics).

Thus the usage of Macaulay reflects an understanding of science as

knowledge that is

contemplative and

formally-learnt, encompassing the broad scope of human endeavor, yet

only somewhat ambiguously focused on situations and methods that are

predominantly the province of natural and mathematical studies. That

ambiguity, though, is in practice dispelled by his summary under the

heading "State of science in England" in 1685. Noting the

foundation, just twenty five years before, of the

Royal Society (whose concerns surely serve as an

indisputable definition of science as natural philosophy), he lists

the subjects of his state of science as including agricultural reform,

medicine, sanitation, " ... the chemical discoveries of

Boyle, and

the earliest botanical researches of Sloane. It was then that Ray made

a new classification of birds and fishes, and that the attention of

Woodward was first drawn toward fossils and shells. ... John Wallis

placed the whole system of statics on a new foundation. Edmund Halley

investigated the properties of the atmosphere, the ebb and flow of the

sea, the laws of magnetism, and the course of the comets; ... mapped

the constellations of the southern

hemisphere"

12.

With the sole

possible exception of Petty's "Political Arithmetic", an early

treatise in economic statistics, what Macaulay refers to are topics in

natural science.

Figure 1.3: St Paul's cathedral, in London, designed by Christopher

Wren, a founder of the Royal Society, and Professor of Astronomy

at Oxford, illustrates the harmony of

natural science, technology, art, and

Christianity in 17th century England.

In the 1898 edition of Macaulay's History, however, a particularly

telling passage appears in the introduction written by

Edward

P. Cheyney, then Professor of European History at the University of

Pennsylvania, and himself the author of an important Short

History of England (1904). Cheyney writes

Figure 1.3: St Paul's cathedral, in London, designed by Christopher

Wren, a founder of the Royal Society, and Professor of Astronomy

at Oxford, illustrates the harmony of

natural science, technology, art, and

Christianity in 17th century England.

In the 1898 edition of Macaulay's History, however, a particularly

telling passage appears in the introduction written by

Edward

P. Cheyney, then Professor of European History at the University of

Pennsylvania, and himself the author of an important Short

History of England (1904). Cheyney writes

There are two quite different views of historical writing. The one

looks upon it as a form of literature, an artistic product, the

materials for which are to be found in the events of the past; the

other considers it as a science, the solution of the problems involved

in the same events of the past. Macaulay represents the former rather

than the latter. If strict canons of criticism were applied to his

methods of investigation and writing, much of his work would fail to

stand the test. ... Abundance of illustration and analogy frequently takes

the place of a really exhaustive study of the sources.13

It is remarkable that a historian would refer to history, or at least

history written in the way he approves, as a science. The differences

between the subjects and methods of history and those of natural

sciences are, as we shall later explore, about as stark as they can

be. But for our present purposes the key question is, what Cheyney is

getting at when he refers to historians that "treat history as a

science" and use "more rigorous methods" while, in contrast to

Macaulay they show "almost entire lack of literary ability"? In the

first place, it seems Cheyney's complaint is that Macaulay is not

rigorous, or critical enough. When he says "There are few things in

history quite so certain as he [Macaulay] seems to make them" his

advocacy appears to be for greater tentativeness. And when he says

"... a spirit of candor and a habit of judicial fairness, was not by

any means a characteristic of Macaulay's mind" his criticism appears

to be aimed at historical writing that contains specific perspectives

and judgements of the merits of actions or events. But when Cheyney

portrays Macaulay's writings as if they were some sort of historical

artistic literature or almost historical fiction, he goes far beyond

what is justified. Whatever may be the shortcomings of Macaulay's

work, there can be no doubt that his was a mind of great erudition,

not just imagination. His historical facts concerning the era he

addresses are carefully documented from original sources. Perhaps he

allowed himself greater latitude in speculative interpretation than

the academic historian of 1900 (or for that matter 2000) would

endorse. But it is remarkable and revealing that in the mind of

Cheyney, this makes Macaulay not so much unprofessional, or a

populist, or merely biased, but rather:

unscientific. This attitude is a consequence of

scientism - an effort to distinguish between `true' scientific

historical knowledge on the one hand, and on the other, literature

that fails to qualify as science and hence as true knowledge. In

effect Cheyney is claiming the credentials of science in support of

his view that some of Macaulay's interpretations are

erroneous.14

Perhaps we can understand Cheyney's position better in the light of

his Presidential address to the

American Historical Society, some 26 years

later15. In this oration entitled Law in

History, although he no longer uses the word scientific to describe

it, he still sees history as on a path to discovery of practically

deterministic cause and effect.

So arises the conception of

law in

history. History, the great course of human affairs, has been the

result not of voluntary action on the part of individuals or groups of

individuals, much less of chance; but has been subject to law. ...

Such are the six general laws I have ventured to state as discoverable

by a search among historical phenomena: first, a law of continuity;

second, a law of impermanence of nations; third, a law of unity of the

race, of interdependence among all its members; fourth, a law of

democracy; fifth, a law of freedom; sixth, a law of moral progress.

May I repeat that I do not conceive of these generalizations as

principles which it would be well for us to accept, or as ideals which

we may hope to attain; but as natural laws, which we must accept

whether we want to or not, whose workings we cannot obviate, however

much we may thwart them to our own failure and disadvantage; laws to

be accepted and reckoned with as much as the laws of gravitation, or

of chemical affinity, or of organic evolution, or of human psychology.

Cheyney's claims and terminology seem aimed to promote

professionalism in history: implying that there

are certain scientific norms of

historiography

practiced by the academic historian, but not by writers of much

broader experience such as Macaulay.

The effort is not convincing. The distinction between academic and

popular

history might be significant, but to

portray this as a distinction between scientific and unscientific is

mostly a power play. The distinction bears no discernible relationship

to methods of the natural sciences. It is mostly a substitution of the

judgement `correct' by `scientific' for rhetorical effect. Given the

present common usage of `science', any merit that might once have

resided in references to

scientific history

is today replaced by confusion. And the hope that some historical law

of (say) "moral progress" would be accepted "as much as the laws of

gravitation", seems to a scientist just silly.

Metaphysics a Science?

The confusion of usages of the word science

throughout the twentieth century may be illustrated by reference to

the insightful An Essay on Metaphysics by R.G.Collingwood

(1940)16. I think it is fair to say that

today metaphysics would be regarded as a subject that stands in

contrast to science. Common sense usage would say something along the

lines that science is about the experimentally verifiable facts of

nature, whereas metaphysics is about the speculative, unverifiable,

logical, and philosophical questions that include

religion and the big questions of human

life17. For Collingwood, though,

classical usages of the words are primary. He explains that literally

metaphysics is simply the expression used by the editors of

Aristotle to describe the writings that are placed

after physics.

Collingwood defines

science (in contrast to common usage even of 1940) as any "body of

systematic or orderly thinking". And he calls metaphysics "an

historical science" which attempts to find out, for the thinkers and

arguments it analyzes, their absolute presuppositions.

Ironically Collingwood is himself aware of and concerned to critique

scientism. He addresses a nineteenth century philosophy whose prime

tenet is that the "only valid method of attaining knowledge is the

method used in the natural sciences" as

Positivism. Undoubtedly the use of

`Positivism' is historically correct and precise terminology to

describe the school of philosophy to which it refers. One reason I

avoid it in talking about the larger issue is that scientism is far

broader and more influential than the explicit formulation by

Auguste Comte (1798-1857) and his followers,

which Collingwood analyses. No, scientism is not just philosophical

and sociological positivism; it is much more pervasive than that. Nor

is it just postivism's twentieth century extension

Logical Positivism, which holds, in

brief, that propositions other than scientific ones are meaningless,

and which Collingwood colorfully criticizes under the title of the

"Suicide of Positivistic Metaphysics"!

I'll have more to say later about these philosophical formulations.

But my present point is that calling metaphysics a science, despite

the practice adopted by Diderot in the mid 18th century, is by

modern standards just plain confusing, since metaphysics is in large

measure defined by the fact that it is not natural science.

Nothing leads more quickly to sloppy thinking and misunderstandings

than terminological confusion of this type. Indeed, the continued

robustness of scientism is surely partly attributable to this

terminological confusion. If science means simply

knowledge, then scientism is just tautologically true. End of

story. But if

science means a particular

type of knowledge, as it does today, then it is essential to recognize

that meaning and stick to it. For this reason and others, as a matter

of the use of language, when I refer to science, I will mean

natural science, not simply systematic knowledge. Moreover I

mean modern natural science, the inheritor of the revolution in

natural philosophy that started in the sixteenth century. I implore

the reader to bear this meaning firmly in mind.

New Sciences

A further source of confusion lies in recent

trends in academic disciplines to refer to their subjects as various

types of "sciences".

It was not a scientist but a philosopher

(John

Searle) who remarked that most of the disciplines that have the word

science in their name are actually not science. He was overstating the

idea, even for the 1970s. But he was making the point that most

subjects that are unequivocally sciences have descriptive names that

don't require the qualification "science". One can think of physics,

chemistry, astronomy, biology, geology, zoology, botany, genetics,

physiology, and so on. No one would hesitate to classify these as part

of science.

In contrast, think about Social Science, Management Sciences, Pharmaceutical

Sciences, Archaeological Sciences, Animal Science, Food Science,

Behavioral Sciences, Decision Sciences, Family and Consumer Sciences

(I am not making these up!) even Computer Science. Practically none

of these are science in the sense of the word that I am using, either

because they are not natural (about nature) or because they are really

technologies or professional studies.

In recent years, it must be conceded, some of the more traditional

sciences have taken to using the word science in the titles of

academic departments (e.g. Earth Sciences, Biological Sciences,

Atmospheric Sciences, Materials Science, Marine Sciences, Life

Sciences) but in most cases this seems to be either because they

represent a merging of several historically distinct subjects, or

because they want to shed a narrow interpretation.

Whatever may be the individual justification, the outbreak of

"sciences" in academic descriptions is in part a reflection of

scientism at work. If science is all the real knowledge there is, as

scientism says, then a self-respecting academic department better be

sure that its discipline is understood to be science. But of course, a

discipline does not become a science by simply calling itself one. So

not all the new "sciences" are science in any useful sense. But what

does make a discipline a science?

1.3 The Scientific Revolution

Please consider buying the book to read on.